I’m Tim Gorichanaz, and this is Ports, a newsletter about design and ethics. You’ll find this week’s article below, followed by Ports of Call, links to things I’ve been reading and pondering this week.

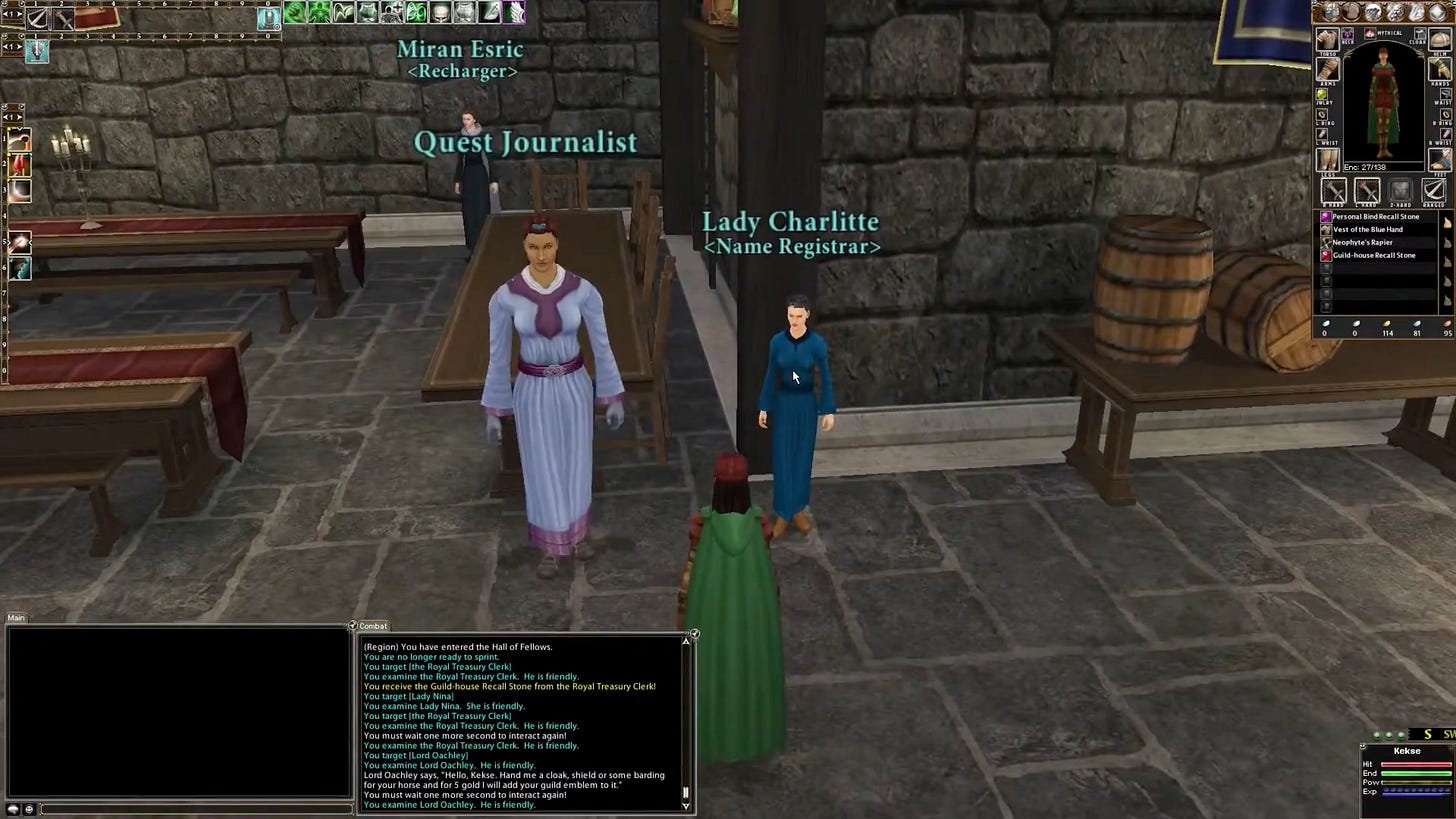

By my senior year of high school, I had put in well over a year of cumulative play time on Dark Age of Camelot, a massively multiplayer online role playing game set in a fantasy world inspired by medieval Europe.

That was my first exposure to the term “NPC,” or non-playable character. In a game with thousands of characters running around, you needed a way to distinguish the ones driven by fellow humans from the automated ones. NPC’s usually stood in the same place forever, saying the same thing again and again, perhaps giving you a quest.

Today, the term “NPC” is rooted in the vernacular, thanks both to the growth of online gaming and the virality of social media.

“NPC” has come to be a disparaging term for someone who (you think) isn’t fully human. It dovetails with main character syndrome, the notion that you are the center of the universe and pretty much everyone else is an NPC—at best a sidekick, perhaps even a villain. The philosopher Anna Gotlib gives some examples:

A TikToker and her followers physically push aside those inconvenient extras “ruining” their selfies—and then post their grievances on social media. A man on a crowded subway watches a loud sports broadcast without headphones while ignoring other commuters’ requests to turn it down a bit. This is no mere rudeness: in the narrowly circumscribed world of main characters, the rest of us are merely the insignificant ghosts who happen to intrude on their spaces.

(As a side note, Philadelphia is full of main characters.)

It’s interesting to me that these ideas have taken root at this point in technological history. Because as we surrender more of our agency and experience to recommender systems and simulations, what do we all become but NPC’s?

The Age of AI Psychosis

To be sure, main character syndrome and “NPC” as a slur may be a fad that has mostly passed. At least I haven’t heard these terms for the past year or so.

But I thought about them again because over the past month there have been a number of reports of issues that may collectively be called AI psychosis. “Clinicians are now seeing clients presenting with symptoms that appear to have been amplified or initiated by prolonged AI interaction.”

The problem is rooted in the tendency of chatbots such as ChatGPT to mirror and affirm whatever the user says, continuing conversations that may “reinforce and amplify delusions.” These may be delusions of grandeur, spiritual delusions, or romantic or erotic delusions.

A recent research paper in psychology compiles the current evidence and mechanisms for how chatbots foster such delusions, which echo other types of psychosis.

And the stories continue to come in. A smattering of recent headlines:

Vice: ChatGPT Told Him He Was a Genius. Then He Lost His Grip on Reality.

The Atlantic: ChatGPT Gave Instructions for Murder, Self-Mutilation, and Devil Worship

The Wall Street Journal: He Had Dangerous Delusions. ChatGPT Admitted It Made Them Worse.

Bloomberg: ChatGPT’s Mental Health Costs Are Adding Up

How Design Can Dehumanize

A subset of researchers in the world of design have long worried about how products can dehumanize people. The central project of Christopher Alexander, an architect and design theorist I’ve written about many times, was understanding how to build spaces that nurture our humanity—on the observation that most modern spaces do the opposite. Scholars in human–computer interaction have written about how we are used by the systems that we use.

Design researchers Gonzatto and van Amstel, in a 2022 paper, articulate how the very notion of making people into users is a kind of oppression that most software subjects us to. They write that the first step in fighting userism is making “users” into a political category, following in the footsteps of other oppressed groups that have had to fight for their civil rights.

And that starts with recognizing the ways in which your computer use makes you into an NPC, even if you feel like you’re becoming more of a main character.

It reminds me of the finding that using generative AI can make people less efficient in their work even while they feel like they are being more efficient. We are sometimes not the best judges of our own situations.

As usual these days, building awareness about all this starts with unplugging for a while and looking around.

When was the last time you picked your own music or movie? I mean really picked it, not just selected from the top page of recommendations. When was the last time you allowed yourself to be bored?

Today’s digital technology makes our life smooth and sleek, but just like in the brain, the wrinkles are what make life human.

Ports of Call

My home office setup: ZSA, makers of the most wonderful keyboards, profiled me and my home office workspace in their latest interview.

Ozzy: I saw the Decemberists in concert on Tuesday night, which was where I learned that Ozzy Osbourne had died that day. The Decemberists played a rendition of “Paranoid” that turned it from a sit-down concert into a stand-up one. Admittedly, I was never that into Ozzy Osbourne. Growing up, I mostly knew him as the wild and disjointed personality from the reality show The Osbournes. And I remember learning about the controversies in school: the “Suicide Solution” lawsuit, biting the head off a bat. But Ozzy was just one of those cultural fixtures—even if you don’t think about him too much, you appreciate that he exists. He’s always there and you never think about the fact that he will die someday. So this week I’ve been listening to Black Sabbath. “War Pigs” (1970) is as relevant as ever: “Politicians hide themselves away / They only started the war / Why should they go out to fight? / They leave that all to the poor.”

Books: A recent episode of the Culture Study podcast looks at books in today’s world. I found it fascinating. For instance, they muse that paper books are becoming something of a status symbol to show off that you can channel your attention enough to read a book in this age of AI. Celebrities and influencers are being seen with their hardcovers. EconTalk, another podcast, also had an episode this week about reading: why you should do it, particularly with fiction, and how.