I’m Tim Gorichanaz, and this is Ports, a newsletter about design and ethics. You’ll find this week’s article below, followed by Ports of Call, links to things I’ve been reading and pondering this week.

Sometimes pens move themselves. At least it seems that way, when you’re in class or at a meeting, pen-tip poised over paper like a bird about to take flight. And then you find yourself—not taking notes, but scribbling gibberish.

If you’re me, that gibberish is usually a particular cursive letter, probably a capital, repeating again and again. Sometimes it’s a field of cross-hatches, or an amoeba. And slowly the gibberish grows and morphs as it reveals itself like a crown jewel in the margin.

Most people are doodlers—perhaps all of us are. And though in the past doodling got a bad rap as evidence that the doodler was bored or not paying attention, there’s been research suggesting that doodling bolsters cognitive performance on listening, and that doodling (along with fidgeting) aids in creativity through improved mind-body regulation.

I think sometimes about my students, who bring laptops to class instead of paper notebooks (this quarter, with one exception). Are they missing out on something? With a laptop one’s fingertips can poise like a whole flock, and yet we don’t doodle on a keyboard.

Doodle Theory

Some places make us feel alive, others dead. We all know the feeling of a green terrace with dappled lighting and a gentle breeze, and how that contrasts with the grim geometry of a municipal office building flatly lit by those fluorescent tubes. We can find the same contrast in works of art—some work, some don’t—and pretty much everything humans create.

Christopher Alexander was an architect and design theorist who wanted to understand why this was. Could this difference be described with principles, perhaps mathematically? (He was a mathematician before he became an architect.) The result of his decades-long exploration of this question is The Nature of Order, a few-thousand-page opus split into four volumes. In this work, Alexander explains how beauty can be described with fifteen properties, and how beauty emerges through a process not unlike how a biological organism grows, which he called the fundamental differentiating process.

Perhaps unexpectedly, Alexander says the process can be exemplified by doodling.

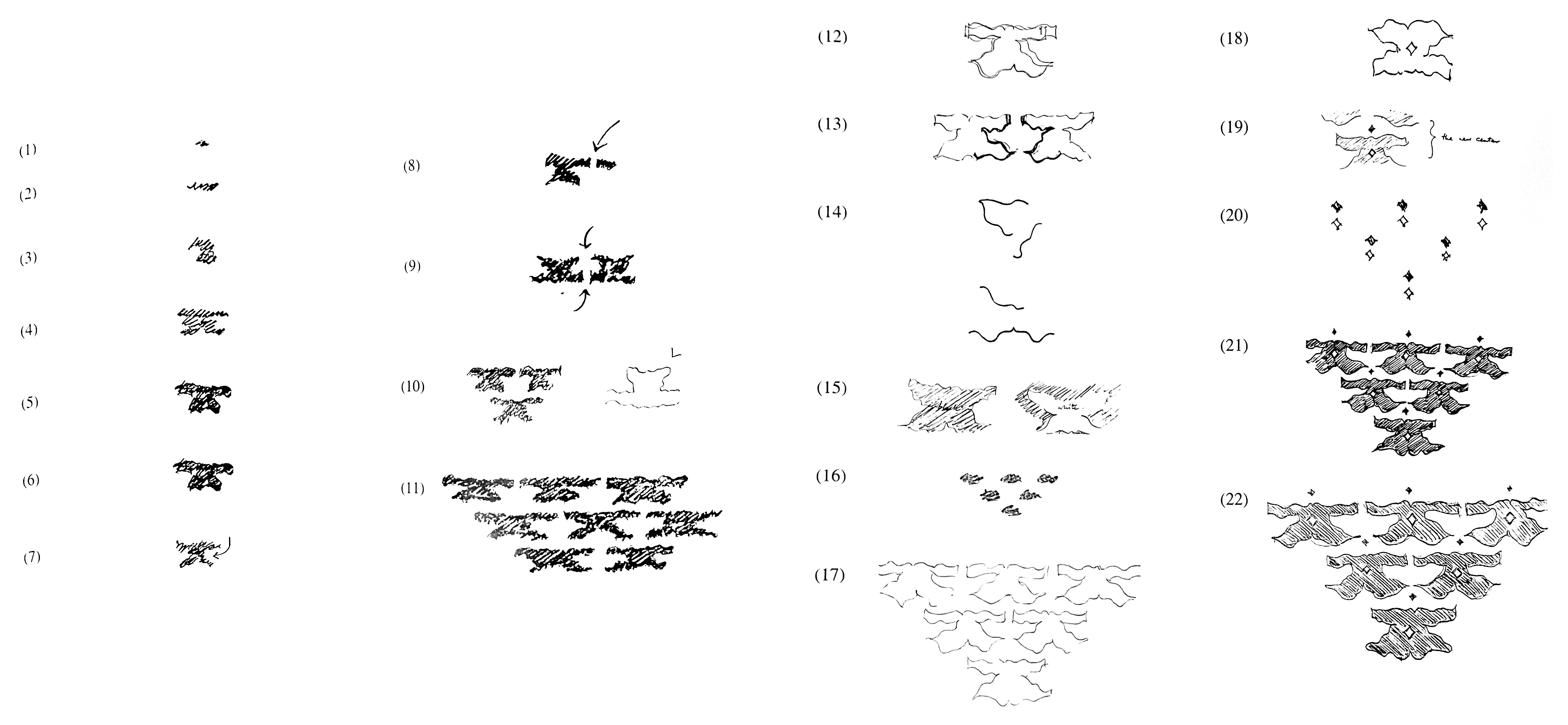

Halfway through the second book, he demonstrates. “I went into it very, very fast, so all of what happens, happens so fast I am not in control, and the process is almost autonomous.” Alexander starts with a single dot, which he then enlarges. The angle of his arm makes the dot grow into a thick horizontal line, which he then accentuates. The pencil slips, and he incorporates that error into the growing shape, and on and on. All the while, Alexander is attentive—almost unconsciously so—to the emerging form, and his pencil’s next move always seeks to enhance that shape—to allow it to become more of itself, even as what “it” is doesn’t exist until it emerges. Eventually Alexander notices that the shape is conducive to patterned repetition—the white space between the shapes nicely mirrored the shapes themselves—and he explores that.

As the process continues, Alexander explores how to refine the shapes, giving them a more pleasant presence, and then going further to give each individual shape “more force, and to knit the whole fabric together.”

You can see this progression in the image below, excerpted from the book. In steps 1–11, Alexander stumbles upon the general motif. In steps 12–17, he refines the shape to be repeated. And in steps 18–22, he finalizes the pattern by adding ornaments that enhance the shapes.

Feeling and Design

The process here, described more generally, is the following: Always do the best thing next. From wherever you are, taking into account the shape of things around you, do the smallest thing you can that will make the overall arrangement better and not worse.

This is not an intellectual matter. It’s not about measuring or making a list of pros and cons. It’s about feeling. Unapologetically so. And that’s what good design comes down to, whether we’re talking “good” in terms of aesthetics, usability, accessibility or morality: Good design is about observing your feelings, and being able to consider the whole and also the parts at once.

What doodling teaches us, then, is that good design is not some arcane skill that only the highly-paid eccentric priests can do. It’s something we all do, because we all doodle (once we put the laptops away, anyway).

And though the doodling and feeling tend to get squashed out of us by a certain age, we can find it once again, because it’s still inside us.

So do some doodling, and then consider how you can apply that same sensibility to the other things you do. That’s what doodling can teach us.

Ports of Call

A Finale: Ted Lasso ended this week, with the finale of season three. In my view, it was a perfect wrap-up to a wonderful series. If you haven’t watched it, please do: It’s the story of what can happen if we are kind and forgive, even when that’s these are the hardest things to do. I cried during most episodes of this show, especially in this last season.

A Playlist: Japanese Jazz When Driving on a Warm Night. It’s what it sounds like. A 45-minute playlist that I keep coming back to, especially for creativity-sparking background music for certain activities in my classes.

A Keynote: From the iPod to the iPad, I used to watch all the Apple keynotes live. I’ve done so less and less as the years have gone on. But I’ll be watching the WWDC keynote scheduled for this coming Monday. Apple is rumored to announce their secretive and expensive mixed-reality headset.

On Depopulation: The Economist has a spate of recent articles about population decline. Apparently birthrates in Africa are falling, meaning that the peak human population to come in a few decades may be lower than expected. The chart below, from this article, was also illuminating—it shows the relative population growth (or decline) of a handful of nations over the coming 80 years. It’s a strange time to be alive: On one hand we’re experiencing the dawn of the internet, which will only come once in the history of humanity. On the other hand we’re at the brink of another fundamental shift; for all our history so far, the human population has been rising, and that is about to change.

I appreciate this edition of Ports and its take on doodling! I know that I was an avid doodler throughout school. It was an integral part of my notetaking process! I remember times when I would share my doodles with peers and we would compare what each of us had drawn during class. Instead of comparing notes and what we had learned, we would compare our doodles. Looking back to those school days I can still remember some of the doodles I had done but can hardly remember what course it was!

From the earliest times I can remember, when I doodled, I would utilize the environment to the best of my ability. For instance, staying within the margins was an important rule for me since they were visible lines that set boundaries. (I didn't want to interfere with the actual notes that I took.) Also, I took notes in 3-punch hole notebooks, so many of my doodles incorporated the holes on the left side as part of my design process. I learned how to use my environment and use it in my doodles.